Ten years and two weeks ago I moved to my beloved city. I loved my city from the first time I walked the streets of downtown.

Ten years and two weeks ago I moved to my beloved city. I loved my city from the first time I walked the streets of downtown.

I loved the diversity and knowing I lived in a city that boasted of citizens who were royalty in their home countries, whose families included exiled peace leaders, and those who had fled genocide and war. I loved that they felt free to share their stories.

I loved that we all lived so peacefully together—all colors and creeds—it made no difference.

I loved the seemingly colorblind utopia that I had found.

On July 4, 1999, I learned that the fringes are never colorblind. On the edges of my idyllic community resided a hate that lived deep. As a white, mostly middle-class American, that is something that rarely touches me. But there it was; it erupted and spilled into my beautiful home. On the steps of the Korean Methodist Church, just blocks from my own church, shots rang out and a beautiful Korean man fell dead.

I remember that shock so clearly. I couldn’t understand, couldn’t comprehend, how or why someone would do something so horrible. The tragedy didn’t end here. The gunman in our midst continued on his deadly path shooting every black, Jew and Asian he saw. By the time the weekend was over, two men lay dead and nine were recovering from gunshot wounds.

The thing that initially puzzled me the most was, why here? Of all the places, of all the cities that embrace diversity and culture, why did the gunman have to be a resident here? Why did he choose to move here and try to spread his hatred?

I was still young when that occurred and for a while I was able to compartmentalize the event and say it was an isolated event. He was an outsider with an agenda. But as time passed and I was drawn into the Asian community, especially the Korean community, my illusions of calm were shattered.

There was always unrest on the fringes. The Korean man I dated often told me of the times he would go to the lake and have racist comments yelled at him. How, when he drove to neighboring cities, he was pulled over without provocation. His friends were quick to share similar stories—each different and horrible.

I would like to withdrawal into my white, American, mostly-middle class life and believe once again that these are isolated events. But I know better now. I’m aware now.

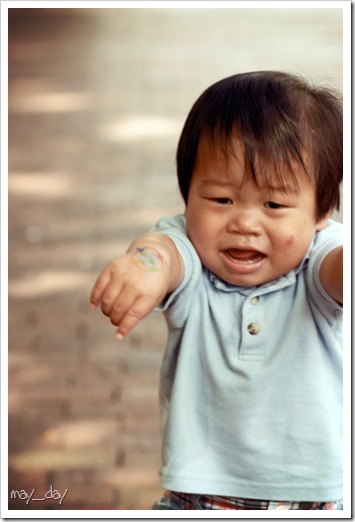

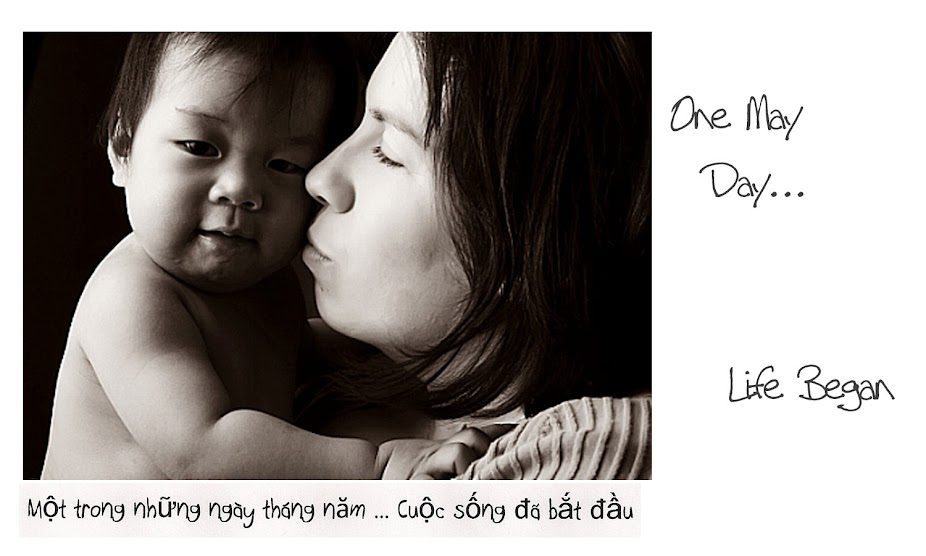

When I look at my son’s face, I don’t see a Vietnamese face or an Asian face, I see the face of my son. I see his perfect golden skin, the dimples that he flashes too easily, and his deep brown eyes that sometimes flash a hint of blue.

As a parent of an Asian child I can not pretend that hatred does not exist. I saw it ten years ago, I experienced it five years ago with a boyfriend and I have seen it already with my son. Ignorance and stupidity are not good excuses for racism and yet I find myself excusing certain people’s behavior because they are redneck, hillbilly trash. I explain it away because I want to keep the peace—at work and with my sister’s in-laws. But when does that racist stupidity mutate into the hatred that we experienced? What is the catalyst?

It has been ten years since that horrible day and I have thought of that event every 4th of July since. This year, it almost slipped by, the year that it should have mattered most to me. None the less, I stand as a witness to the brutality and hate of that day. Two strangers, both outsiders to our little city, both gone in a weekend. I never knew either one—victim or killer—but in the two weeks that we resided in the same city our paths might have crossed a number of times.

This weekend thoughts of that day are never far from my mind. This 4th of July I plan to hold my son close, pray that God protect him, and pray for the day when no parent has to worry about their child’s safety because of the color of their skin.

The pictures says it all, does it not?

The pictures says it all, does it not?